Welcome to RealTime Mandarin—a multimedia resource to immerse you in the latest Chinese language trends, inspire you to practice and improve your Mandarin every week, and empower you to communicate with confidence.

Subscribe now to get the next issue straight to your inbox!

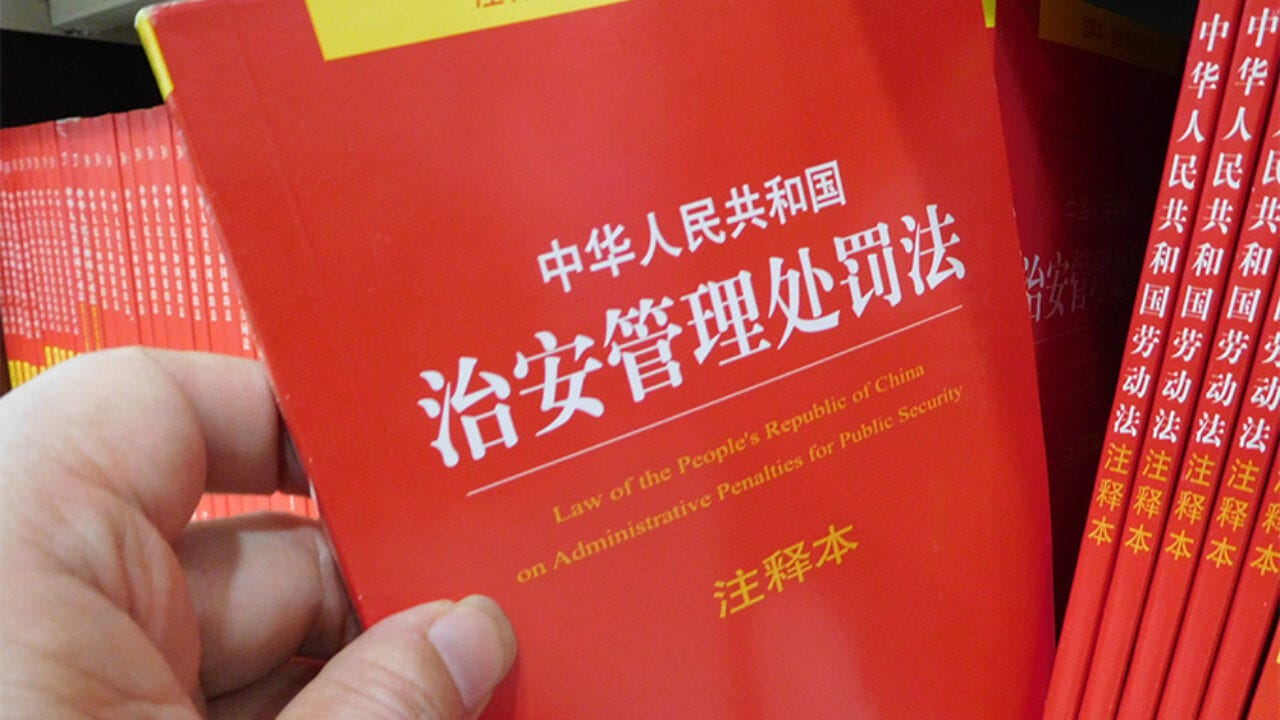

A draft amendment to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law (治安管理处罚法 zhì'ān guǎnlǐ chǔfá fǎ) was published on the Chinese People’s Congress website on 5 September.

The draft is published for public consultation (征求意见 zhēngqiú yìjiàn) before China’s lawmakers finalize changes to the law.

One proposal in the draft has sparked debate in China:

In this revision, the second and third paragraphs of Article 34 indicate newly added behaviours that should be punished, including "wearing in public places clothes and accessories that are detrimental to the spirit of the Chinese nation, and hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation”; and "producing, disseminating and publicizing things or remarks that are harmful to the feelings of the Chinese people".

在该修订中,第三十四条的第二款和第三款意见显示了新增应处罚的事项,包括“在公共场所穿着、佩戴有损中华民族精神、伤害中华民族感情的服饰、标志的;制作、传播、宣扬、散布有损中华民族感情、伤害中华民族感情的物品或者言论的。”

Punishments under the draft changes include detention of up to 15 days and fines up to 5000 yuan.

But what counts as “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people”?

It’s vague and subjective, as one commentator notes:

The meanings of "harming the spirit of the Chinese nation" and "hurting the feelings of the Chinese people" are ambiguous. If implemented, it may be a typical "pocket crime" which is likely to be abused.

“有损中华民族精神”、“伤害中华民族感情”含义模棱两可。如果实行的话,则可能是典型的“口袋罪”。有可能同饱受争议的寻衅滋事罪和曾经的流氓罪一样,极大可能被滥用。[1]

And it's reminiscent of another over-used and abused legal instrument, which we have learned about in this newsletter: 寻衅滋事 xún xìn zī shì - “provocation and troublemaking”.

So, where will these proposed changes to the law stop when it comes to hurting the feelings of the Chinese people…?

Here’s a selection of entertaining comments from social media posts:

What exactly do you mean by “clothing and accessories that hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation”?

Does wearing a suit harm the spirit of the Chinese nation?

Or is the performance of the Chinese men's football team over the past decade considered "damaging the spirit of the Chinese nation"? Does it not call for subjective judgement to determine the crime and dish out punishment?

“伤害中华民族感情的服饰、标志”到底指的是什么?

穿西装是否有损中华民族精神?

又譬如中国男足这十几年来的表现,又算不算“损害中华民族精神”?

认定并处罚那算不算带有主观意识?[2]

So that’s what we explore this week!

Favourite Five

1. 含糊 hán hu

vague, unclear

草案条款概念含糊,没有明确的界定标准,成了热议的焦点 - The concept behind the draft clause is vague, with no clear defining criteria, which has become the focus of heated discussions. [2]

Related:

模糊 mó hu - blurry, fuzzy

含糊其辞 hán hú qí cí - vague

2. 口袋罪 kǒu dài zuì

pocket crime

如果实行的话,则可能是典型的“口袋罪” - If implemented, it could potentially be a classic "pocket crime". [1]

More: A legal term for “catch-all” laws that are easily abused. Read more in The China Project.

3. 模棱两可 mó léng liǎng kě

ambiguous

第二款、第三款中提到的“有损中华民族精神”、“伤害中华民族感情”含义模棱两可 - The meanings of "harming to the spirit of the Chinese nation" and "hurting the feelings of the Chinese nation" mentioned in the second and third clauses are ambiguous. [1]

4. 人人自危 rén rén zì wēi

everyone feels insecure

别说自由言论,就是任何一句话都可以装到极其模糊的概念里,人人自危 - Forget about freedom of speech; even a single sentence can fall under this extremely vague concept, making everyone feel insecure. [2]

5. 欲加之罪,何患无辞 yù jiā zhī zuì, hé huàn wú cí

when you want to accuse someone, there's no lack of a pretext

如果公职人员可以凭个人偏好和观念信条,随意扩张解释和适用法律,那么我们距离“欲加之罪,何患无辞”也就不远了 - If public officials can interpret and apply the law arbitrarily based on their personal preferences and ideological beliefs, then we are not far from the situation where "when you want to accuse someone, there's no lack of a pretext." [3]

Note: A well-known colloquial phrase which originates from The Commentary of Zuo (左传) written during the 4th century BC about the Spring and Autumn period in Chinese history.

Consuming the Conversation

Useful words

6. 筐 kuāng

basket, category

该观点认为一些法律人质疑寻衅滋事是法律的耻辱,是个筐,什么都往里装,实际这是巨大的误解 - This viewpoint believes it is a gross misunderstanding that some legal experts view picking fights and starting quarrels as a disgrace to the law, because it is like a basket where everything can be thrown in. [2]

7. 压制 yā zhì

suppress, oppress

进一步恶化公共领域的舆论环境,不当压制个人在日常穿衣与言论的自由空间 - It further poisons public discourse and improperly suppresses individuals' freedom of clothing and speech. [2]

8. 无边 wú biān

boundless, limitless

无疑就是肆意扩大处罚范围,最终导致权力无边 - Undoubtedly, it is an arbitrary expansion of the scope of punishment, ultimately leading to boundless power. [2]

9. 溢出 yì chū

overflow, spill over

很多新增的违法行为其实已溢出治安管理的范畴 - Many newly added illegal behaviors actually no longer belong to the realm of public security management. [3]

10. 滋生 zī shēng

to breed, to foster (negative connotations)

否则对新兴违法行为的打击和压制很有可能滋生出不受约束和控制的权力 - Otherwise, the crackdown and suppression of newly defined illegal behaviors is very likely to foster unchecked and uncontrolled power. [3]

11. 消弭 xiāo mí

to silence or eradicate

既要清晰地划定需要国家惩罚权介入的领域,也要避免法律与道德边界的消弭 - We need to clearly delineate the areas where the state's punitive power should intervene while also not blurring the boundary between law and morality. [3]

12. 汉奸 hàn jiān

traitor, collaborator

我认为那篇文章没有伤害谁,但是后台确实有不少人攻击我是“汉奸” - I believe that the article didn't harm anyone, but there were indeed many people accusing me of being a "traitor". [3]

Three-character phrases

13. 流氓罪 liú máng zuì

hooliganism, thuggery