Welcome to RealTime Mandarin, a free weekly newsletter that helps you improve your Mandarin in 10 minutes a week.

Subscribe today to get your fluency back, stay informed about China, and communicate with confidence in Chinese — all through immersion in real news.

China launched a new visa category on October 1 aimed at attracting young professionals from abroad.

The new “K-visa” (K签) makes it easier for highly skilled foreign nationals—specifically “science and technology young international talent” (外国青年科技人才)—to stay in China for up to five years without being sponsored by an organisation.

It’s positioned between ordinary work “Z-visas” and the high-end talent “R-visa”. Compared to the R-visa, it has much lower requirements for education and work experience. And compared to ordinary work visas, the K-visa allows more entries into China and a longer length of stay.

The K-visa was first announced on August 7, but the public reaction was muted. When it officially launched at the start of October, however, it triggered widespread discussion on Chinese social media.

That was partly a reaction to how it was reported in India, and then how that reaction was reported inside China.

An Indian media outlet framed the K-visa as an alternative to America’s H-1B skilled worker visa, which was recently restricted to make it harder for foreign nationals to enter the US. The change particularly affected Indian applicants, who received 71% of H-1B visas last year.

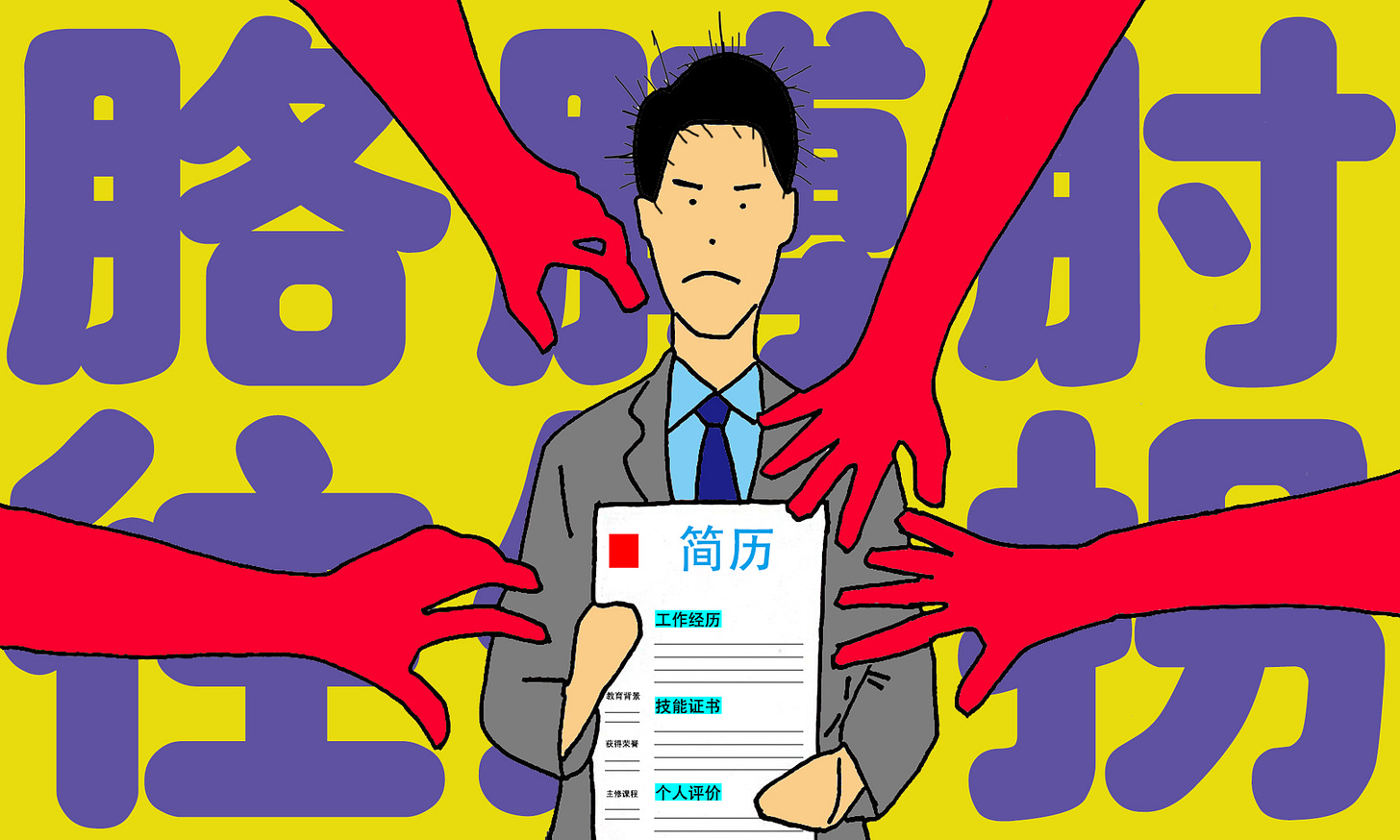

The apparent excitement in India about this new K-visa quickly sparked high anxiety in China, where concerns grew that it could prompt an influx of Indian graduates competing for jobs with Chinese nationals in an already difficult employment market.

This tapped into nationalist sentiments among some people in China, which were unhelpfully amplified by figures like Hu Xijin (胡锡进), former editor of the Global Times:

“I’m begging the Chinese embassy and consulates in India to be more stringent in issuing K-visas.

In principle such visas should not be granted lightly to Indian graduates.”

拜托中国驻印度使领馆把K签证的印章看紧了,原则上轻易不能给他们的毕业生发K签证。

Related

The Chinese government has not yet released full details about the K-visa, which is part of the problem.

Misunderstanding, fear, and even conspiracy theories have spread on social media, with tens of thousands of people criticising the program, concerned that it will become even harder to land a job.

Behind this strong response are broader anxieties among young professionals.

As we’ve seen in this newsletter, China’s job market is under pressure, with many young people unable to find work. Youth unemployment is around 19%, and a record 12.2 million college graduates are competing for jobs this year. Even those who do find work often end up stuck in low-paid “workhorse” (牛马) roles.

So for many, the K-visa represents yet more competition. They want the government to focus on China’s young talent first—to create employment opportunities for young Chinese before prioritising outsiders:

Young Chinese who are anxious about job prospects find this policy hard to comprehend and perceive it as an act of turning its back on its own people.

在正愁找不到工作的中国年轻人眼里,仍然会是难以理解的”胳膊肘往外拐“政策

As anxieties have continued to rise, some sensible voices in the media are trying to lower the temperature.

They argue the fear is misplaced. One article asks the right question: Why would someone from India actually want to move to China?

The highly competitive, often underpaid, high-stress working environment isn’t exactly appealing to bright young graduates looking for a better life.

And even if foreign talent did come to China, would it be any easier for them to find a job?

That’s unlikely.

The article also highlights an important detail buried in the otherwise vague policy: foreigners holding K-visas cannot be employed in China. Young graduates cannot simply enter the country and “take” jobs from Chinese job-seekers.

Instead, the visa allows three types of activities: exchange (交流), entrepreneurship (创业), and business (商务)—all of which could create employment opportunities for Chinese nationals, not eliminate them.

However, there are valid concerns about the risks of the program.

The biggest concern, partly exacerbated by the lack of detail around standards, process, and vetting, is that the new visa could be open to abuse. Such as by foreign applicants using fake documentation to pose as highly qualified when they’re not.

Even more concerning, say some, is the potential for Chinese nationals to exploit the system. For example, young Chinese who graduated abroad could pose as overseas applicants to gain preferential access to jobs or business opportunities in China.

These concerns revolve around how those with privilege, inside and outside China, might game the system for their own advantage at the expense of ordinary workers—just like “Miss Dong” (董小姐) did earlier this year.

So it’s a complicated picture, and it’s what we’re discussing this week!

Favourite Five

1. 抢占 qiǎng zhàn

seize, grab

大量普通学历的年轻人涌入中国抢占工作机会 - A growing number of lower-educated young people are flocking to China for jobs that locals increasingly struggle to find. [2]

Related: 挤占 jǐ zhàn – crowd out

2. 杞人忧天 qǐ rén yōu tiān

overthink, worry unnecessarily

抵制K签担心自己饭碗的人,基本上是杞人忧天 - Those who oppose the K-visa out of fear for their jobs are basically worrying over nothing. [4]

Related:

惊弓之鸟 jīng gōng zhī niǎo – a frightened bird, easily startled

风吹草动 fēng chuī cǎo dòng – slightest disturbance, sign of trouble

3. 野鸡学校 yě jī xué xiào

diploma mill, unaccredited school

不是什么野鸡学校的毕业生都能随便申请到K字签证来中国的 - China doesn’t hand out K-visas to just any graduate from a dubious university. [2]

Related:

水硕 shuǐ shuò – unqualified master’s degree

水分 shuǐ fèn – falseness, lack of substance

4. 胳膊肘往外拐 gē bo zhǒu wǎng wài guǎi

side with outsiders against one’s own, turn their back on their own people

在正愁找不到工作的中国年轻人眼里,仍然会是难以理解的“胳膊肘往外拐”政策 - Young Chinese who are anxious about job prospects find this policy hard to comprehend and perceive it as an act of turning its back on its own people. [2]

5. 请神容易送神难 qǐng shén róng yì sòng shén nán

It’s easy to invite a god, but hard to send one away; easy to invite but hard to get rid of

请神容易送神难,拖家带口来的、赖着不走的 - As the saying goes, it is easy to invite a god but hard to send one away — many arrive with their families and show little inclination to leave. [3]

🎧RTM Podcast Preview

This week on the RTM Advanced podcast, we explain phrases which mean “worrying too much”.

“fear disorder” (恐惧症 kǒng jù zhèng)

“worry unnecessarily” (杞人忧天 qǐ rén yōu tiān)

“overreact out of fear” (因噎废食 yīn yē fèi shí)

Tune in at 7 minutes where we break down what they mean and the stories behind them…

How native speakers use them…

And how you can use them in real conversations right now and show off your amazing Chinese!

Consuming the Conversation

💡 Ready to get inspired to bridge the gap to real-world fluency? 💡

In every RTM Advanced post you unlock content and tools to inspire you, and help you get fluent.

So, ready to finally get started and wave goodbye to that nagging rusty feeling?

Let’s jump in👇

Useful words

6. 掺杂 chān zá

mix, blend

恐慌情绪与民族主义掺杂在一起 - Panic is intertwined with nationalism. [1]

7. 完爆 wán bào

completely surpass, crush

有些开卡车一类的蓝领工作收入完爆普通白领 - Some blue-collar workers like truck drivers earn way more than a regular white-collar employee. [1]

Note: internal slang phrase originally from gaming

8. 效力 xiào lì

serve, work for

增加一个签证类别,方便更多来自全世界的年轻人才来华效力 - The new visa category makes it easier for young talents from around the world to come and work in China. [2]

Note: not to be confused with 效力 (noun) in the legal context meaning “effect” or “validity”, for example, “legal validity” (法律效力).

9. 镀金 dù jīn

embellish credentials, seek prestige

其中包括水平不高专门来中国名校镀金的留学生 - That includes underqualified foreign students who come to China’s top universities just to boost their credentials. [2]

10. 愤慨 fèn kǎi

indignant, angry

一时半会儿找不到正经工作的中国年轻人,面对来抢工作的外国年轻人,心态必定会更加委屈和愤慨 - Young Chinese struggling to land decent jobs are bound to feel increasingly frustrated and resentful when confronted with foreign youths competing for the same positions. [2]

11. 警觉 jǐng jué

alert, vigilant

就是这段话,引起了国内网友的警觉 - It was this very statement that raised alarm among Chinese netizens. [4]

12. 脑补 nǎo bǔ

imagine, fill in the blanks mentally

不少看到这条消息的国人开始脑补 - Many Chinese who saw this news began to speculate wildly. [4]