Welcome to RealTime Mandarin, a free weekly newsletter that helps you improve your Mandarin in 10 minutes a week.

Subscribe today to get your fluency back, stay informed about China, and communicate with confidence in Chinese — all through immersion in real news.

The Nanjing Museum has been a trending topic on Chinese social media feeds over the last week.

It’s one of China’s most prestigious cultural institutions. Referred to as Nanbo (南博) for short in Chinese, it is at the centre of a scandal involving missing national treasures, fake identities, and allegations of systematic theft spanning decades.

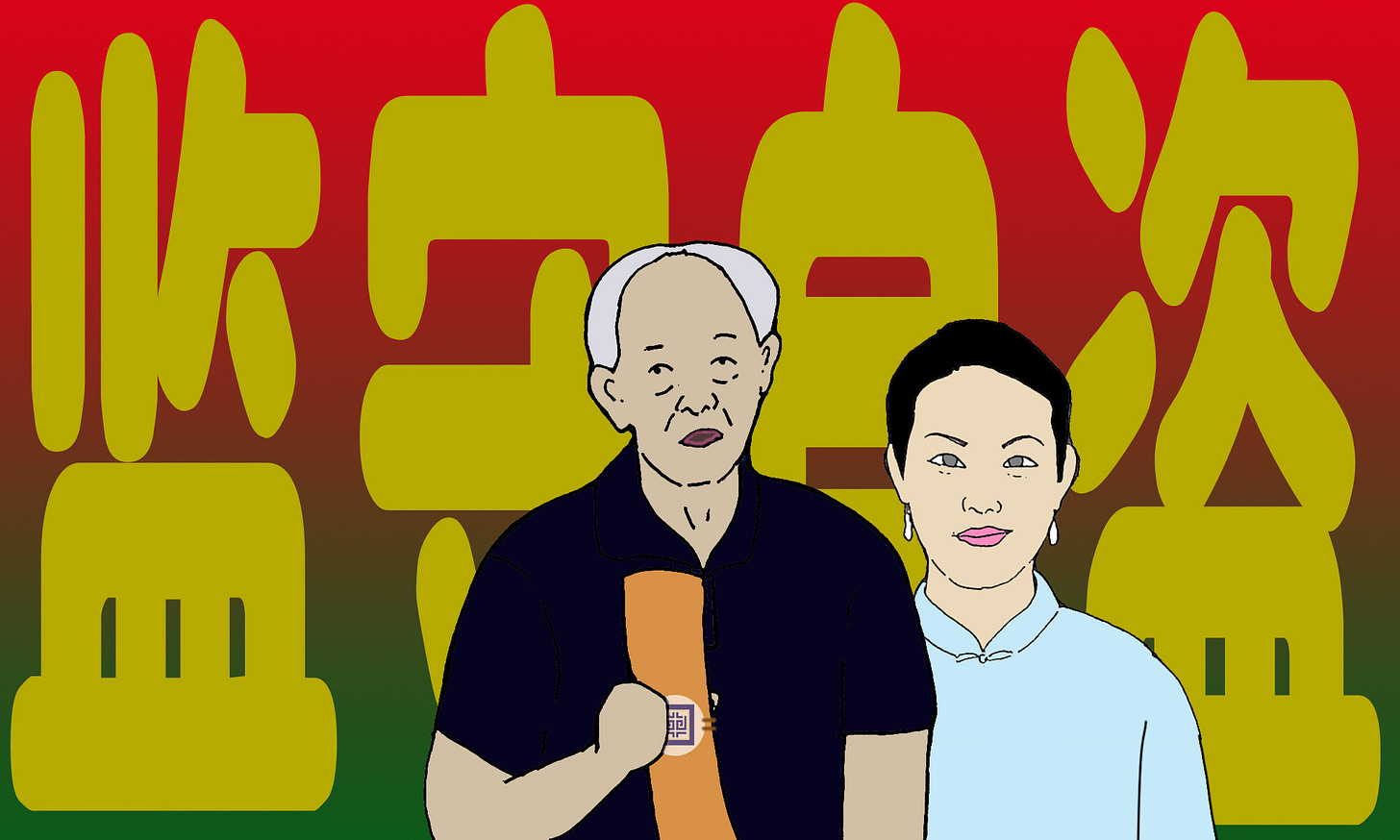

In late December, a whistleblower report from a retired museum employee circulated online, alleging that former director Xu Huping (徐湖平) orchestrated a scheme to steal thousands of national treasures by declaring them “fakes” (伪作) and then selling them through family-controlled channels for a profit.

Rumours soon swirled online that Xu had been arrested.

When contacted by media, Xu’s response was vague and raised further suspicions. In a video message from his home, he said:

“I’m already in my 80s, currently sick at home. After I retired in 2008, I stopped being involved in external affairs. I didn’t handle this matter, and I’m not an appraiser anyway.”

“我都80多岁了,现在生病在家,2008年退休之后,我就不参与外界的事了,这事也不是我经手的,我也不是鉴定家。”

So nothing to see here, apparently. But something in the video seemed off.

Sharp-eyed antiques enthusiasts noticed a number of precious cultural relics in the video background. These were items that, if authentic, would be worth a fortune, and should be in a museum.

Related

These recent events are linked to story which began in June this year, when a Ming Dynasty painting called Jiangnan Spring (江南春) appeared at a Beijing auction house with an estimated price of 88 million yuan ($12.1 million).

That painting had been donated to the Nanjing Museum decades ago by the family of one of China’s most celebrated and wealthy art collectors, Pang Laichen (庞莱臣). When he died in 1949, Pang left behind “treasures valuable enough to buy half of Shanghai” (足以买下半个上海的宝藏).

In 1959, having decided to stay on the Mainland rather than flee to Taiwan, where the Nationalists had transported thousands of imperial treasures from the Forbidden City, Pang's grandson Pang Zenghe (庞增和) and the family donated 137 pieces from the family collection to the Nanjing Museum. Among the donated works was Jiangnan Spring (江南春), a landscape painting by Ming Dynasty master painter, Qiu Ying (仇英).

Back to June 2025. When Pang family representative noticed the Jiangnan Spring at the Beijing auction house, he informed the auctioneer who removed it, then he contacted the Nanjing Museum and demanded an explanation. Days later, when Pang family representatives arrived at the museum, they discovered five paintings, including Jiangnan Spring, from the original collection of 137 were missing.

According to the Nanjing Museum, these five works had been appraised in 1961 and 1964, and declared “fakes” (伪作). In 1997, these five “fake” paintings were transferred to the Jiangsu Cultural Relics Store. And in 2001, according to store records, the Jiangnan Spring was sold for just 6,800 yuan. But the records listed the buyer only as “customer” (顾客), with no further details.

The numbers didn’t add up: a painting sold as worthless in 2001 for 6,800 yuan was now valued at 88 million yuan in 2025.

The whistleblower report outlined how the alleged scheme worked: former director, Xu Huping had the donated paintings appraised as forgeries, then sold them at extremely low prices to the Jiangsu Cultural Relics Store, where he served as legal representative. Subsequently, his son, who operates an auction house in Shanghai, resold these cultural relics at market prices domestically and internationally.

As the scandal unfolded, another name kept appearing: Xu Ying (徐莺). She had been claiming to be a “Pang family descendant” (庞莱臣后人) since 2014, having curated a Pang collection exhibition at the museum, with the endorsement of Xu Huping.

Xu Ying’s role in this alleged scheme remains unclear, but her fraudulent identity orchestrated by Xu Huping as a “Pang descendant” would have provided valuable cover. And the fact her family name is the same as the older Xu’s, is also suspicious.

The parallels to one of 2025's biggest scandals didn't go unnoticed: "Miss Dong" (董小姐), a trainee doctor who allegedly used family connections to secure a coveted medical training position. Social media users quickly dubbed Xu Ying "Nanjing Museum's Miss Dong" (南博董小姐), suggesting she similarly exploited family ties for career and financial gain.

The Nanjing Museum case exposes a fundamental problem in China’s cultural heritage system, as one observer put it:

“Once donated, the property rights of treasures are also transferred to the organisation they are donated to.

Although the museum legally had disposal rights, but legal doesn’t mean ethical.”

捐赠了,物权转移了,处置权在法理上或许没错,但于情错了。

So that’s what we’re exploring this week!

Favourite Five

1. 赝品 yàn pǐn

fake, forgery

这5件藏品当年被鉴定是假货,是赝品 - These five works of art were authenticated as fakes and classified as forgeries at the time. [1]

Related:

伪作 wěi zuò – forgery

假画 jiǎ huà – fake painting

2. 水很深 shuǐ hěn shēn

complicated, murky

原来以为文物单位是清清白白干干净净的,没想到也有这么深的水 - We thought museums were beyond reproach, but it turns out the waters run far deeper than expected. [1]

3. 浮出水面 fú chū shuǐ miàn

to surface, to come to light

昨天一个叫“徐莺”的女士渐渐浮出水面 - Yesterday, the name “Ms. Xu Ying” gradually came to light. [1]

Related:

水落石出 shuǐ luò shí chū - to come to light, to be revealed

崭露头角 zhǎn lù tóu jiǎo - to emerge, to start standing out

4. 监守自盗 jiān shǒu zì dào

stealing from one’s own post, an inside job

郭礼典的指控,指向了一场系统性的、大规模的监守自盗 - Guo’s accusation pointed to inside jobs done systematically and at large scale. [2]

5. 近水楼台 jìn shuǐ lóu tái

to have an advantage due to proximity, to have easier access

她自己作为庞莱臣的“后人”,研究自家老祖宗的书画收藏,当然是近水楼台了 - As a descendant of Pang, she naturally has easier access to her own family’s collection of calligraphy and paintings. [1]

🎧RTM Podcast Preview

This week on the RTM Advanced podcast, we explain different words which mean “fake” in Chinese, including:

“fake, forgery” - 赝品 (yàn pǐn)

“forgery” - 伪作 (wěi zuò)

“imitation” - 仿品 (fǎng pǐn)

Tune in at 7 minutes where we break down what they mean, how native speakers use them…

And how you can use them in real conversations right now and show off your amazing Chinese!

Consuming the Conversation

💡 Ready to get inspired to bridge the gap to real-world fluency? 💡

In every RTM Advanced post you unlock content and tools to inspire you, and help you get fluent.

So, ready to finally get started and wave goodbye to that nagging rusty feeling?

Let’s jump in👇

Consuming the Conversation

Useful words

6. 蹊跷 qī qiao

suspicious, strange

一位庞莱臣的后人看到这幅画后觉得十分蹊跷 - A descendant of Pang Laichen found it very strange upon seeing the painting. [1]

7. 贱卖 jiàn mài

to sell cheaply, to dump at a low price

《江南春》转手后,以6800元的价格“贱卖”了 - After changing hands, “Jiangnan Spring” was sold for just 6,800 yuan. [1]

8. 国宝 guó bǎo

national treasure

是不是用这种方法偷偷把国宝变成私人财产 - Did they use this approach to secretly turn national treasures into private property?[1]

9. 高人 gāo rén

master, mastermind

回望她过去的时间线,才发现,徐莺的背后有“高人” - By retracing her career, it becomes clear that there was someone else pulling the strings behind the scenes. [1]

Related:

后人 hòu rén - descendant, later generation

10. 站台 zhàn tái

to publicly support, to endorse

他亲自到场为徐莺站台 - He personally showed up to endorse Xu Ying in public. [1]

11. 冒充 mào chōng

to impersonate, to pretend to be

徐莺冒充庞家人身份,这背后,都有徐湖平的手笔 - Xu Ying impersonated a member of the Pang family, and all of this was orchestrated by Xu Huping. [1]